Hi everyone! I'm Jordana Composto, a Postdoctoral Fellow with DIBS in the Marketing and Behavioural Science Division at UBC Sauder. I joined UBC after completing my PhD in Psychology and Social Policy at Princeton University.

I study how people make sense of the social world around them—what's acceptable, what institutions should do, and what policies we should support. Most of my work focuses on climate change and the energy transition. At DIBS, I'm exploring how individual actions and system-level solutions can work together in complex, real-world systems.

As a first-timer at the BIG Differences BC conference, I am blown away by the quality and range of behavioural research this community is producing.

Let me tell you a bit about yourselves. You—yes, you brilliant conference attendees—are part of a group of 1,575 people from 56 countries. Through Stephanie Papik's morning Circle Practice, you created a space built on respect, curiosity, and presence. And you lived it: we saw 1,954 Zoom reactions throughout the day!

Wordcloud generated through Slido from the morning Circle Practice.

My 3 takeaways from BIG Difference BC 2025:

1. Complex ≠ Complicated

Though often used interchangeably, "complex" and "complicated" describe fundamentally different problems requiring different approaches.

Complicated problems are like baking a pie. There are many ingredients and steps, but there's a definitive recipe. The solution is knowable, repeatable, and predictable. You might mess up the crust your first time, but once you master the technique, you can bake the same pie again and again with consistent results.

Complex problems are like running a restaurant. No solution works the same way twice. The system is dynamic and adaptive—what delights customers this month might bore them next month. Staff dynamics shift, food costs fluctuate, or a viral social media post changes everything overnight. The components interact to create emergent outcomes you couldn't have predicted from analyzing each piece separately.

These categories aren't mutually exclusive, but the distinction changes how we approach solutions.

BI can tackle complexity simply. The challenges we're working on—inequality, healthcare access, climate change, education—exist in dynamic systems requiring ongoing adaptation. But working on complex challenges doesn't mean abandoning core BI values. Keep it simple.

Complex systems resist detailed prediction and control, so use simple principles: probe and sense (try small things, learn fast), embrace multiple perspectives, iterate constantly, and trust local knowledge. A behavioural scientist tackling vaccination uptake doesn't start with a comprehensive master plan. They ask: "What small change could we try this week?" Then watch, learn, adjust.

Study complex systems because that's where human challenges actually live. But keep your insights clear, your experiments well-defined, and your language accessible. Let solutions emerge rather than forcing predetermined answers. The goal isn't to conquer complexity—it's to work with it, gracefully and simply.

2. Evidence-Based Policy Must Be a Two-Way Street

The relationship between researchers and policymakers needs to be bi-directional from the start.

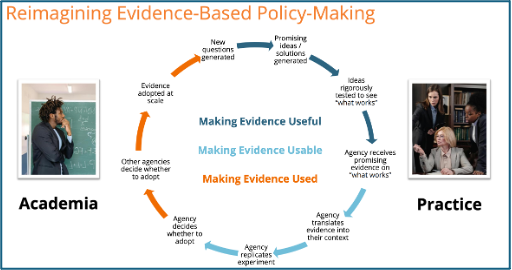

In her keynote, Dr. Elizabeth Linos challenged us to reimagine evidence-based policymaking. The traditional narrative positions researchers as knowledge producers who "translate" findings for practitioners. This framing is well-meaning but incomplete.

Dr. Linos identified a critical gap: "While the academic community is producing policy-relevant research—research with clear policy implications—we are falling short of producing policy-impactful research that changes which programs are adopted and how services are delivered at scale."

Diagram from Dr. Linos’ keynote.

The disconnect stems from different priorities. Researchers typically optimize for effect size and experiment precision. Policymakers operate within a more complex decision space: budget constraints, political feasibility, community buy-in, heterogeneity of results across subpopulations, implementation capacity, and evidence of real-world success.

A study demonstrating a 15% improvement may be rigorous and significant, but it loses relevance if it costs twice the available budget, requires training capacity that doesn't exist, or shows inconsistent results for certain population groups.

Academics need to understand policymaker constraints before designing studies, not just at the dissemination stage. Policymakers need to articulate what makes evidence actionable in their context. Both sides benefit when research questions are shaped by the realities of implementation from day one. Understanding what makes research policy-impactful—not just policy-relevant—is how we ensure evidence actually improves lives at scale.

3. Build an Adaptable Playbook

In the words of Lindsay Miles-Pickup: "The beauty of behavioural science really lies in its adaptability. Our understanding of human behaviour is constantly evolving, and so too must our playbooks and the tools that we use."

Move beyond the standard behavioural insights toolkit that focuses on the moment of decision-making for the individual. We need to consider the complex systems that shape behaviour and decisions.

Practical approaches from the conference:

Map the whole system, then zoom in. The behavioural systems mapping approach shared by Dr. Jennifer Macklin lets you see the entire system while focusing on specific behavioural problems. This helps you develop bundles of interventions that address multiple parts of the system simultaneously, rather than isolated fixes that might create unintended consequences elsewhere.

Weave worldviews together. Dr. Emily Salmon (Unxiimtunaat) reminded us that different worldviews hold their own histories, strengths, and priorities. Like weaving threads, we shouldn't lose individual perspectives—we should combine them to create patterns of resilience and beauty that no single strand could form on its own. This is especially crucial when working across cultures and communities.

Use mixed methods strategically. Dr. Rhiannon Mosher offered guidance on when and how to integrate qualitative methods into your project lifecycle—not as an all-or-nothing choice, but as strategic additions where they add the most value.

Let AI be your research assistant, not your researcher. Sasha Tregebov showed how AI can efficiently handle literature reviews and support qualitative analysis—freeing you up to focus on interpretation, intervention design, and the human judgment that complex problems require.

Don't overlook basic BI. While behavioural science expands to include system-level interventions, simple, individual-level tweaks still deliver impact. As Dr. Tak Ishikawa put it: if you can implement something that makes life simpler for people, just do it! Don't wait for the perfect test or the most innovative approach. This community values practical, credible work alongside ambitious research. Sometimes the solution worth running is the obvious one.

Closing thoughts:

These three themes—embracing complexity with simplicity, building true partnerships between research and practice, and staying adaptable in our methods—reinforce each other. They remind us that behavioural science works best when it stays grounded, practical, and responsive to the messy reality of human systems.

Thank you to the BIG Differences BC community for creating a space where these insights could emerge. The respect, curiosity, and presence you brought to the conference embody exactly how we should approach the complex challenges ahead.

About the Author

Dr. Jordana Composto

Jordana is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business, working with the Decision Insights for Business & Society group and the Centre for Climate and Business Solutions. She received her PhD in Psychology and Social Policy from Princeton University. She holds a BA from Dartmouth College in Quantitative Social Science and Environmental Studies.